The Connection Between Breath and the Pelvic Floor

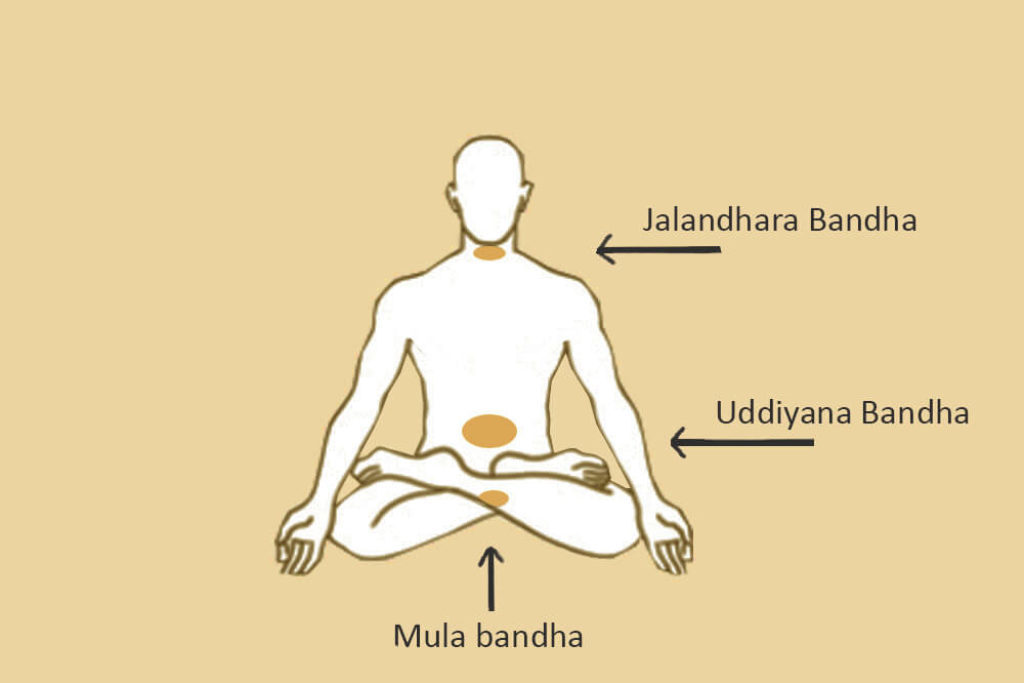

Bandhas

In yogic philosophy, our bodies have bandhas, or locks. We each have three of them, and one master lock for engaging all of them at once. In yoga, these locks are places of movement in the body that can be held or tightened to affect our energy. In the Western world, we actually share some of these anatomical beliefs, but under a different name. We call them diaphragms. And similarly, they can be places of movement or they can be locks of our energy and breath. You may think that this sounds strange, since most people think of the thin layer of muscle separating the chest and abdominal cavity as the diaphragm. While it is true that this is our respiratory diaphragm, there are two other diaphragms in the thorax that move and respond to our breath and force production.

To summarize, the three diaphragms of the body are:

-

The glottis in the throat

-

The respiratory diaphragm

-

The pelvic floor muscles

I talk a lot about the glottis as a lock in my post on the intra-abdominal pressure system. The main takeaway for the sake of this post is that the glottis can be opened or closed to allow air in and out, or to lock it in place. If our abdomen was a bottle, the glottis would be the cap. To breathe, we must have an open glottis and (ideally) allow our diaphragm to contract and descend towards our abdomen to pull air into our lungs.

The other two diaphragms of the body, the respiratory diaphragm and the pelvic floor, work very closely together in their movement to help us control our breath and to remain continent (AKA holding in pee). So if I were to be palpating (manually feeling) a woman’s pelvic floor muscles and asking her to breathe deeply, this is the relationship I would likely feel:

As a woman takes a deep breath in, the respiratory diaphragm descend into the abdomen and creates pressure down onto the pelvic floor, making it also stretch and descend slightly. Then as she exhales the air out by allowing the respiratory diaphragm to relax and return to its original dome shape, the pelvic floor naturally and passively draws up slightly and engages, or contracts. This is the ordinary ebb and flow of the two lower diaphragms of the body. It is a simple way that we can easily manage the intra-abdominal pressure system.

Fear of Movement

I have worked with some women who fear allowing any movement and stretch of the pelvic floor, because they don’t want to leak urine. I wrote more about stress incontinence here. These women tend to either be chronic breath-holders or very, very guarded and constantly squeezing through their pelvic floor. This is quite dysfunctional. We need to breathe with our respiratory diaphragm freely moving for many reasons. If we don’t allow it to move, this can lead to back and neck pain, inefficiency in breathing, and poor movement patterns. Just as in yoga, our breath is our energy source!

So how can we allow our diaphragm and pelvic floor to move freely? How can we keep from locking out and tensing them constantly? And how do we keep from leaking with movements that naturally make our pelvic floor muscles stretch? It is called an eccentric contraction.

Eccentric Contraction

An eccentric contraction is where a muscle is lengthened and contracted. Imagine curling a dumbbell with your biceps muscle. The muscle engages and shortens as you lift the weight up towards your shoulder. But, the muscle is also engaged as you slowly (and with control) lower the weight back down. This is the eccentric component of the movement, called a negative in weight lifting. Of course, you could lift the weight up and then just completely turn the biceps off and let the weight drop, requiring no control. But usually, we keep the muscle turned on as it lengthens and lowers the weight.

This concept of an eccentric contraction holds true with the pelvic floor. We can allow this lowest diaphragm of muscle to raise and lower with our breath and movement, while still contracting it as we need to be continent.

If a woman was bracing her pelvic floor and constantly engaging the muscles so that they couldn’t stretch and descend, then her respiratory diaphragm would be pushing down onto her pelvic organs without any place for them to go except smashing into the pelvic floor. (Think of one of those machines for smashing a pop can. The arm presses down into the can with no place for it to go but up against the rigid bottom surface. So the can takes all of the force and crumbles.) This can be aggravating to pelvic organ prolapse or hemorrhoids, if a woman has either/both.

Ironically, while women may begin to brace and lock out their pelvic floor in order to keep from leaking, in the long run, all of that pressure down onto the pelvic floor muscles can actually lead to more weakness or pelvic pain. This is a recipe for exacerbating incontinence!

So what is the key to bringing balance and ease to the movements of the diaphragms?

Breathing!

It seems simple, but training our breath to be slow and controlled helps to coordinate the movements of the respiratory diaphragm and the pelvic floor muscles. While you may have some leakage or notice the stretching of the pelvic floor after you stop aggressively contracting all the time, remember that this movement is safe. And the more it is practiced, the more your body will figure out exactly how much it needs to contract the pelvic floor to keep urine in.

Mindfulness

Taking time each day to practice mindfully relaxing and releasing the pelvic floor muscles is a great way to bring more awareness to when they are tight and when they are relaxed.

Time

If you are guarding and blocking movement of the respiratory diaphragm or the pelvic floor because of trauma like childbirth, be patient with yourself as your tissues heal.

Physical Therapy

If you continue to have difficulty with breathing while moving, with relaxing the pelvic floor, and/or with incontinence, then seek out a physical therapist who can help you with more customized exercises and training for your recovery. It is a worthy investment in yourself!